Welcome to my diary for my book series Wildebyte Arcades! Here I explain how I came up with the idea(s), how I wrote the books, what problems I faced, and more. Hopefully it’s educational and fun to read.

This was my first “English fiction experiment”. I wanted to start writing my novels in English and thought a relatively simple series of (short) children’s books would be the best practice.

Let’s get started!

What’s the idea?

Story

The Wildebyte was somehow (magically) teleported into the world of video games.

When we start the series, they’ve been living in that world for some time. They’ve forgotten who they were before. They are simply a character in whatever game they’re in. Playing Pacman? Wildebyte might be pacman, but they might also be a ghost. Playing Mario? Wildebyte might control Mario. Playing Candy Crush? Wildebyte might be a candy. You get the idea.

And they love that. They have a “never think, just do”-mentality. They just throw themselves at every problem, adventure, obstacle, game mechanic. That’s why they were never really motivated to find a way out of this curse—if it even is a curse.

Lastly, because of this, other characters in this world refer to them as “The Wildebyte”, because they are so wild and unpredictable and they are absolutely terrified of this kid.

(Notice how I refer to the character as they. Because they take over any character inside a game, they might be a young boy in one game, and an old lady in another. And they have forgotten who they were before going into this world, so I can’t refer to that part of their identity.)

Structure

Why did I choose this story?

- I wanted something short and lighthearted. I tend to doubt myself too much and overcomplicate projects. This time, I told myself: “no deeper meaning, no plan, just write adventures within video games”

- I’ve been toying with the idea of a fantasy story __of somebody inside games. It seemed suitable for me, as I both write and develop games.

- I wanted to differentiate from existing (similar) stories. Many stories start with a character’s normal life … until they are suddenly teleported to a new magical world by the end of chapter 2 or 3. Usually, such stories continue by immediately adding some huge evil that rules these lands, and the character’s biggest desire is to go back home. I wanted to break free from this! And therefore, you start already inside the world and the main character doesn’t even know to what life they’d go back.

Additionally, I wanted each part to be standalone. By mostly ignoring an overall arc (such as “learning about this new world” or “good vs evil”), you can read any book in any order.

I am shooting for at most 50,000 words per book. Chapters will be shorter than usual. Each book tries to focus on one type of game, not necessarily one game. (Any one game has dramatic potential, but usually not enough to sustain a full novel.)

Where to start?

Oh boy, this was hard. Until, after a few days, I realized it wasn’t.

I researched the most popular video games, especially among kids, and thought I’d just pick the number one spot. But it’s not that clear what the number one spot is! Different statistics and different ways of measuring … yield different results.

Instead, I wrote down the general popular trends:

- Shooting / Battle Royale (like Fortnite, Fall Guys)

- Sports (like FIFA or Rocket League)

- Creative (like Minecraft, LEGO, Roblox)

- Casual (like Candy Crush, Farmville, Subway Surfers)

- Classic (like Mario, Pong, Pacman)

If I start with a shooter, I’ll probably lose a large part of my target audience. Especially because it’s parents buying the books (in general).

Sports is one of the “common categories”: liked enough by pretty much everyone. (If you want a family-friendly, wide-appeal game, base it on a sport.) At the same time, playing a character inside a sports game is … well … quite similar to just playing a sport in real life. Therefore, starting with this would not introduce the unique world well enough.

The same for creative games: they are too creative. Some players might really “gamify” it, others might stick to building stuff they know from real life.

And finally, classic games are known by my generation (and the generations around it), but less so by the newer generations. Me and my friends grew up playing many variants on Mario, Pong and Pacman on upcoming online gaming websites. Kids these days will only have a vague idea about who Mario is.

This leaves us with casual games played on a smartphone. This category is much bigger than you think (in terms of games, users and profit). It is another “common category”. Most people know the popular games and will even have played them, both kids and adults.

That’s why I started the series with that.

And then I realized: what am I doing? These are standalone books and we don’t start at the actual start. I can just TRY different openings or stories and place them in any order I want LATER.

So I actually wrote multiple first chapters. More on that later.

Turning this into a novel

Now we only need a few ingredients to kick things off. (Remember, I wanted no plan and no deeper meaning or plot twists or whatever, so we’re just improvising after chapter 1.)

What do we need?

- A good conflict. The Wildebyte wants something, an obstacle stands in their way. It is urgent and impactful: if they don’t act quickly … they’ll lose to the obstacle.

- A fun event in chapter 1 that kicks off the conflict (“inciting incident”)

This was my idea:

- They’re playing a runner game (a parody on Subway Surfers or Temple Run) = action!

- They try their best, but the score just isn’t great, or something goes wrong.

- And then their world goes dark and they can’t play the game anymore.

- What happened? Unsatisfied, the player chose a different character to play.

The general progress in the novel is then:

- The Wildebyte tries to gain back favor and become the leading ( = playing) character in a game again

- As they jump between casual games on the same phone, they also learn about the user. They might read text messages about how “he isn’t allowed to play anymore because his parents forbid it”. They might see more and more games uninstalled.

- So they desperately try to convince the user to keep the games active and on the phone, otherwise they are destroyed as well!

- But in the end, the phone is wiped (by his angry parents, probably), and we end in a climax in which the Wildebyte desperately escapes the phone.

Sounds like a plan. Let’s do it.

The first few chapters

I think my first few chapters contain many great elements, but also many elements that make me doubt the whole story concept :p

For example, it is able to neatly setup the world and explain technical concepts behind games. Without interrupting the story flow at all, and while cracking many jokes.

But at the same time, our main conflict of “gaining back favor” has become a moot point by chapter 5. Why? Because the original game is uninstalled and thus destroyed :p

That’s what you get when improvising. You just go with what seems most interesting at that moment, which might end conflicts early (or start new ones).

So far, each chapter is between 1,000-1,500 words. That’s quite short, but I think it works. Final book will be at most 40 chapters. Current pace is 4,000-5,000 words a day.

Writing these pages revealed that I needed to do a bit more worldbuilding. That always happens: you write a scene, then realize “wait, if we’re actually inside a video game, this is impossible!”. You have found a problem and need to find a nice explanation for it that fits with the universe.

Game development is a skill I actually possess. I know more about the technology behind it than most. That’s why I wanted to focus on that: create a fantasy world that is as realistic as possible, without feeling complicated or boring. A film like “Wreck-It Ralph” focuses on the high-level concepts only—I think my stories can set themselves apart by actually applying knowledge about how video games work.

That’s why I made decisions like these:

- The games are actually blobs in memory. When played, they are teleported to working memory (RAM). When done, they shut down and go back to the hard drive.

- There isn’t a whole “hidden world” inside a video game. The game only does what the code allows, and it has only created models/images for whatever it needs.

- There’s an actual camera moving around. Whatever it captures, is shown on the Player’s screen.

It’s hard to find a balance. Because you also want to allow creativity, personal choice, characters with personality. The story becomes boring quickly if all characters can only respond with the one line of dialogue they have—and nothing else. So I am already inserting some exceptions to the rules that allow this.

A fresh start

The next day, I booted my computer and wrote the sixth chapter. Then I received an email.

I had participated in a writing contest a few months ago and I finally received feedback about my manuscript. It confirmed some of the issues I also noticed with my own writing. (I got 11th place, out of ~40 entries, by the way.)

The major criticism was that the book was too full and convoluted. It tried to do too much. And it actually succeeded in many ways, but it was exhausting to read if that wasn’t “your thing”.

Well … this made me reconsider my current project. I fell into the same trap. I thought “staying in one game the whole book will surely get boring”, so by chapter six, you’ve already entered a different game.

And that’s why I told myself: no, let’s listen to this feedback for once :p

I put aside my current work. I vowed to stick to one game per story. This is possible if I change my perspective. If I don’t view the game as is, but as what it could be (behind the scenes).

What does that mean? Let’s take that runner game. Right now, I just describe what a Player knows and sees. Collecting coins, monster running after you, taking turns and jumping over gaps, character selection. Yes, this will be quite boring and predictable, not enough for a book.

But what if I look further than that? What if I invent other systems, parts of the game, mechanics that could be going on? What if I design my hypothetical casual game to lead to an interesting story immediately?

The new plan

That became the new plan.

- Even shorter books, but each one focused on just one game.

- Chapter 1 clearly outlines the four questions:

- Who is our main character? Wildebyte. A quick recap about their character, if this is your first book.

- What do they want? The Wildebyte always wants to have fun, play games, help anyone in trouble.

- What happens if they don’t get it? This is the hardest one. It depends on the story. Every time, I need to find something terrible that will happen if the issue isn’t solved.

- Who is trying to stop them? This also depends on the story.

- Within at most 20 chapters, we’ve reached a resolution and leave the game (for good).

- There is some slight growth and linearity between books, but they remain standalone.

How do we find conflict? How do we bring The Wildebyte in trouble?

We need to establish some clear rules for them.

- If a game is uninstalled / removed / wiped when they are inside, they are wiped as well

- Enemies or games might change their code and personality, or “lock” the Wildebyte, removing their possibility to have fun and play.

To streamline this, I invented two “organizations” coming after the Wildebyte at all times.

- One actively tries to destroy him—for good.

- One actively tries to pull him out of the game world and help him return hime.

This can be the cause of numerous conflicts 🙂 The first group will do anything to destroy Wildebyte’s current game. The other group will do anything to force him to listen and leave with them.

These organizations are pretty much the only constant factor across all books.

The other way to add conflict, is not to put Wildebyte themself in peril, but characters or things that he cares about. For example, they might meet great people in a game, or really like their current game so they want it to succeed and become popular.

Let’s start again with this fresh perspective.

The general structure

Here’s a general structure for the full list of stories. It focuses on simplest and most well-known / popular games first, and ends with the most powerful devices (which means more complexity but also more opportunity).

- I still want to start with the (hyper)casual games, just one per book. Let’s call that “The Smartphone Era”.

- Then we’ll probably go to consoles and arcades: “The Console Era”

- And finally we get to (super)computers: “The Computer Era”

The Wildebyte starts very enthusiastic, positive and energetic. (In the current version they started quite grumpy and annoyed, actually. Which just feels too … cynical? Not ideal for stories primarly aimed at young adiences?)

But the stakes are also raised. It’s not “hmm this game doesn’t run like I want” or “hmm this game is boring”. From chapter 1, I want to introduce some weird and mysterious event that threatens their whole extistence.

Let’s start again

Book 1: runner games. Temple Run, Subway Surfers, that category.

What could go wrong? While running, something unexpected ends up on the path. Something that isn’t part of the game. When Wildebyte touches it, he notices he is not going to the game over screen, but feels he is being erased. (He loses some part of his code here?) As he saves himself, he notices somebody leaving.

How do we sustain this mystery or sense of progression? Over time we …

- Get further and further into the game. (Later sections, new obstacles, etcetera.)

- Now, with every run, there’s the added danger of accidentally touching that bad thing again!

- Discover different powerups or arenas. Or parts of the palace. Or simply how the game works (both in front and behind the screen).

- Get to know other characters, as Wildebyte tries to discover which of them tried to kill him.

What’s the lesson about game design? I wanted to start with one of the most important ones: “Fun can only come when the player cares.”

I titled this book “The Last Run”. The idea is that the game is very old and hasn’t been updated in a while. Then they learn that they are the last instance of the game running. If they are shut down or uninstalled … they are gone forever. Which is exactly how the book ends. (Which means it’s important for me to actually make you care about the characters.)

Guess what: change of plans

Creativity is an iterative process. I hope this becomes obvious when reading this diary. It’s impossible that the first idea an artist has is flawless and 100% the same as the final product :p

I wrote a few chapters and possible outlines for this book … and realized it still wasn’t great.

- Runner games are quite complex and varied. I still wanted to do too much in this first book of the series. It feels better to start with a simpler type of game and build up to runners in all their popular glory.

- It was hard to explain parts of the world (or game design concepts) when the Wildebyte acts like they’ve been in this video game world (which I started calling Ludra) for a long time. They should be familiar with everything already, so why are they asking questions about it!?

- I wanted to start with simpler and more “core” lessons about games first. It’s too hard to explain why fun comes from caring about something, and really exploring that, in the first book.

What does this mean?

We do start the series with Wildebyte entering this world for the first time. But instead of (the somewhat cliched) “I don’t remember anything about myself or why I’m here”, I want to give more direction.

They have one clear goal in their head “get to the Data Vault”. They are able to communicate (somewhat) with whoever send them into Ludra.

But the game they’re currently in makes this hard. Why? Because the user isn’t playing it. And if you’re not active, you are deactivated and can’t act.

Now we have a clear, simple storyline:

- Make the game fun to play

- So it stays active long enough to escape to the Data Vault.

- (While discovering where the heck that Data Vault is.)

And we have an ending. Yes, Wildebyte succeeds. But he realizes he isn’t actually the hero in this story—he is being controlled by the villains. On willpower, he breaks free and goes rogue. This is the moment he turns into the Wildebyte. (And the ones that controlled him become mad and try to find him in other games to erase him.)

The game we’re working towards is some variation on “Flappy Bird”. It’s widely regarded as the absolute simplest game and the start of the (hyper)casual smartphone game genre.

Last question: what’s the interesting, suspenseful inciting incident from chapter 1? Again, I don’t want to start with 2000 words of: walking around, thinking “where the heck am I”, searching for answers. That is fine for a few chapters down the line, but not the start.

Sleep is wonderful

As always, I realized I was dumb and the solution was staring me in the face … when I went to bed and woke up early the next morning.

The people that put him into the video game world aren’t perfect. They make mistakes. One such mistake, was placing the Wildebyte at the wrong location.

So the first chapters are about them fleeing from dangers and trying to reach the “game” where they were supposed to be from the start. This way, you get action, danger, and you can learn a lot about the world at the same time.

Lastly, I realized a general structure. I’ve learned over the years to employ a “sort of” 4-act structure:

- Suspenseful first chapters, while discovering the conflict and the protagonist

- Then we get our main goal. The storyline along which we progress.

- Until the midpoint. There is some twist, some injection of energy, some new storyline.

- Until we reach ~75% of the book and we get to the climax. Storylines converge, action builds and builds, until the final chapters where everything resolves and comes together in a big bang.

How do we achieve this for this novel?

- Act 1 (rather short): wrong place, have to get to the actual game before something goes wrong

- Act 2: try to make the game better (so it’s actually played), while figuring out how to do the mission (“get into the Data Vault”)

- Act 3: the Wildebyte discovers that not all is as it seems. He discovers dark secrets about the people who put him in there, meets other characters with their own (sad) stories. He keeps working on his goals … but faster and for a different reason.

- Act 4: he fixes the game and makes it fun and playable. That’s how he is able to find the Data Vault. And the story ends with him deciding not to break in, but to flee.

Well … for a story I wanted to write with no plan or deeper meaning, we’re planning quite a lot. So let’s write the first chapters, for the umpteenth time, instead of wasting more time thinking and plotting.

The new first chapters

The advantage of having a clear goal and four act structure, is that writing becomes smooth sailing.

The first few chapters quickly turned into the first half of the book. Things were moving along nicely in every chapter, because I had a clear “step” I wanted to take.

This also makes it a bit more formulaic, so I’ll probably go back (once I have the first draft) and add more description, more vivid language, maybe one more action scene.

What can I say about these chapters? Not that much.

- It was a good choice to start the first book at the actual start. I’ve already invented several things that I know I want to keep in later Wildebyte books. Additions that seem so obvious and logical now … but probably would’ve never come to me if I hadn’t written this start.

- I might want to think a bit longer about how I want to represent the computer world. Now I’m somewhere between realistic and fictional with how I explain things like the CPU or Memory … and that usually means you fail at both aspects.

- I did feel a distinct lack of options and other characters. It felt a bit static and lonely at times. So I wove some other creatures into the narrative without already introducing more (permanent) characters. As the Wildebyte is stuck in their crappy game, there is no good explanation for other intelligent characters visiting or something. So instead, he has some nice interactions with the “Movers” that move around data and install new stuff on the phone.

This book is already very different from anything else I’ve written. English, obviously. But also way more focused on one problem and one character. It will be much shorter than anything I tried before.

I’ve stopped writing the protagonist’s thoughts in italics. I wanted to try it anyway, as I noticed a bad habit of overusing this style. But now the Wildebyte has those researchers in his head controlling him, talking to him, giving instructions. So I decided to write their commands in italics to clearly signal this.

Let me give an example. In other books, I’d do this:

- I skipped Mission Instructions. Hmm, that might have been a mistake.

Now I have to keep Wildebyte’s narrative completely without italics, because they are reserved for the mission leaders.

- I might have made a mistake skipping the Mission Instructions.

- Yes. Yes, you did.

The midpoint

Here we have the turning point for basically all story threads in short succession. And we finally get other characters and more options (as we now have a working game that can be played).

It feels like the story “opens up”—and that is good. It gives the new energy needed to prevent a story from sagging in the middle.

I’ve also started dropping some names or ideas that I know I’ll use in the following books. Starting that “universe building” early :p

I also had to make decisions about certain things I improvised on the fly. Do I continue that one mystery? Do I resolve it in this book? Or should I create an action scene around it to keep things moving?

For example, the communication between Wildebyte and the mission leaders kept cutting out. They state that “someone or something is interfering” and they have to “switch channels constantly”. I wrote that because it worked very well in the scenes and sounded interesting. But why does this happen? No idea.

That’s stuff you need to figure out as you’re nearing the last section of the story. And figure out is the right term, because in my experience these intricate mysteries “come together” as you write more chapters, as opposed to 100% inventing them beforehand.

Like this: as I neared the midpoint, I noticed the story was lacking. I really wanted an extra character, some more tension, and resolution for at least one mystery.

- So I wrote mysterious sounds and footsteps, and later a mysterious bunny crossing through Wildebyte’s game.

- Then I discovered: what if we connect the bunny with the disconnects? Seems fun enough.

- A few chapters later, the researchers talk about testing their technology on animals. That’s a somewhat clear “hint” about the bunny origin, maybe.

- But then the bunny is accompanied by non-living objects.

- And finally we learn that the bunny is a memory of Wildebyte.

- He’s been losing memories, and at this point he remembers NOTHING about his old life. Those memories broke loose from the actual memory of the device (another common thread in the novel) and manifest themselves in this way.

- And then we get to the crucial midpoint event: he briefly manages to speak with the bunny, then the researchers zap it away, basically killing it.

This sets up and solves mysteries, while tying everything together. But I didn’t start with that idea: it happens as you write more chapters.

Across the not-really-midpoint

By now, the path to the ending is mostly filled in. No, I don’t know the details. But I know the general path. I know that everything I set up so far has to come back / play a role in the climax.

And when I made that vague outline until the end, I realized we’re not really at the midpoint, but slightly past it. At the moment, I guess the book will end at chapter 25, while the midpoint is at chapter 15.

(The midpoint was also slightly delayed. The part about “adding Player Input to the game” took way more chapters than I thought: 5 instead of 1 :p. Because the concept was harder to explain. Because someone like Wildebyte would have much more issue with doing this. Because I thought of some fun ways to create really tense scenes.)

Also, there’s no clear reason to stay inside our game any longer. We’ve been there long enough in general, if you ask me.

But the game is also done. It now has a game loop (player input => obstacles => goal), which was the central game lesson with which the book started. It even has theming, decorations, and some extra variation / challenge. Really, you can’t pull many more action scenes out of a crappy Flappy Bird clone.

So chapter 16 is actually the moment everything goes wrong and we leave the game. From that moment, until the end, it’s a mad dash to …

- Break into the Data Vault (and learning even more about the mission and what might be inside)

- While staying away from everybody angry at the Wildebyte

I’ve planned it to be all action, no break. But I know myself, and I will add some breathers and some quiet scenes in there by default. So I think it’ll be alright.

So far, I’ve been hitting almost 5,000 words a day. This means I’ve been writing for only 5 days now, and the book will be done after 9 days.

When that happens, I’ll probably take a break (for several days). Write down all my gripes with the current version, keep a solid library of worldbuilding and ideas for this book series, flesh out the next one or two installments. And then it’s time for the sequel 🙂

What do you mean with worldbuilding? While writing this first book, you realize issues with some explanations, or parts of the world that lack any thought at all. You also figure out who your characters really are—in this case, the Wildebyte is really our only character.

So, in my notes the past 5 days, I’ve been writing stuff like.

- Oh, the Wildebyte should make word jokes all the time.

- Oh, they should steal that map so they can keep it around for the next few books

- Oh, I need a way to represent the different types of input to a device (touch, controller, etcetera)—how??

After a while, these form into more solid ideas, which fit well with each other. I write all that down in some (big) files about the world(s) and the character(s). This way, I won’t contradict myself in the future. And if I forget how part of my world worked, I can quickly look it up.

The Climax

To be honest, at this point I usually run out of steam. Because now I know how it’s supposed to end—I figured that out writing the chapters midway—and so I lose interest :p

I figured out some cool new elements here. For example, I found a good place to explain how flash memory works (the type found in USB drives). And with that explanation, I discovered a cool way to end the book. A way to “pay off” this information.

At the same time, I’m just stringing together action scenes (mostly fighting) and explanation scenes to race to an ending.

I always knew that Wildebyte would not escape. (Otherwise the whole series of books after it cannot exist :p) I always knew the book would end by finally breaking into the Data Vault, but something going wrong (or something being revealed).

When I started writing, I thought that Wildebyte would want to stay. They liked being inside video games too much, so they simply don’t want to go back after the mission.

But now, after 40,000 words, I’ve set up the WIldebyte’s personality to be the opposite. Yes, they thoroughly enjoy playing games. But all other aspects of this world are alien and frustrating to them, and they want to go back to their family and their old life.

Thus, the ending changed. And as always, I tried to make it as interesting and adventurous as possible.

- As you near the end of the book, you get more and more hints that something is off about the mission and the researchers.

- When the Wildebyte enters the Data Vault, they are explicitly told not to look at the data (for some nonsense reasons invented by the researchers).

- When some part of the data does become visible, they read a shocking fact: the researchers simply have no way to bring Wildebyte back to the human world. The technology just isn’t there. They lied. They focused only on their noble goal—which might actually be noble and good—and not on how it would destroy Wildebyte’s life.

- Even if Wildebyte wanted to escape, they can’t.

Interspersed with these revalations is an ongoing stream of action. Obviously, breaking into the vault. Then being stuck inside, surrounded by everyone they made angry throughout the book (that’s a lot of characters), looking for a way out.

I tried to “pay off” all the information you learned along the way. But I don’t want to become formulaic, so I didn’t focus too much on that.

And in the final chapters, I tried to setup some tidbits for the next books. The problem is, though, that I don’t know what the next books are at this point.

First draft

In the end, I think the book is solid, for the most part.

But these are my clear issues that I want to resolve with the first revision:

- Maybe I try to explain too many computer concepts. This also means I can’t delve deep into any of them. This story turned out to revolve around the concept of “memory”, so I probably want to only explain and use concepts related to that “theme”.

- The big “arc” for the main character is about giving away control, versus taking agency and being able to make your own decisions. Right now, there are only a few chapters (at the end) where the Wildebyte is actually fully controlled (by the researchers) and unable to do anything about it. This might not be enough time to get the message/feeling through.

- The book is a bit thin on descriptions, worldbuilding, richness in how things happen. But that is usually the case with me—“get the story/plot out first”—and one of the easier things to add with revision.

Besides that, the book does jump between action scenes rapidly, often finding convenient solutions for problems. But that is by design. I started this project to write some loose, light-hearted adventures. Just a character stuck inside video games, trying to solve a new problem each time. Yes, it goes against my habits and my writing style in the previous books, and that is the point. It is meant as a challenge and a way to broaden my skill set.

Now I’m taking at least a few days off:

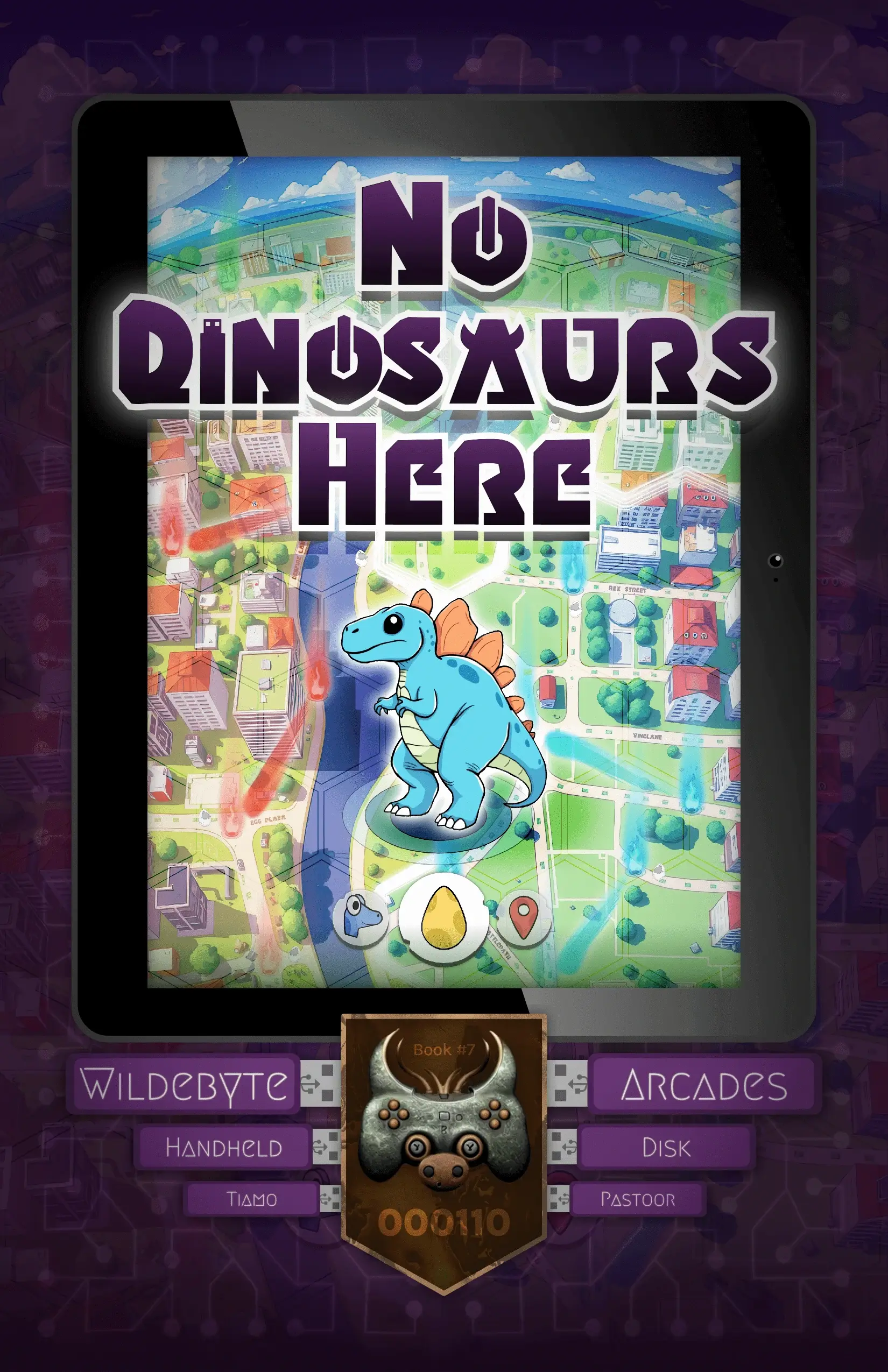

- Listing possible next books

- Trying out some drawings and visual styles for this series. (Font, book cover, perhaps some concept art of each game between the chapters.)

- Maybe draw a map of the device we’re on right now. If not to include it in the book, then for me to keep things organized.

Planning ahead

What am I looking for in the next books? Basically, I want three things:

- A single game in which it takes place.

- A lesson about game dev that will be learned.

- A strong title, subject or conflict. (These influence each other; if I have one, I usually get the others.)

Honestly, the hardest part is finding a good order for these things. Like, I’d love to write a book inside a “Clash of Clans” type game. That game is just made for conflict, adventure, action, etcetera. But it’s also quite a complex game that doesn’t have a general appeal, so is it a good fit for a second book? I don’t know.

Similarly, I can list quite a few game design lessons. But which ones are most important? Which ones should appear at the start?

This is a process that takes time. First, I research and make lists. Then I slowly connect the elements about which I am most certain. And finally, I sort them in an order that brings a steady increase of complexity.

Once I know my second game, I can start the second book 🙂