Welcome to the article in which I explain/track my process for writing book 2 in the Wildebyte Arcades (Rulebreaker Recipes).

Because I aim to make this a long-standing series, I really wanted to flesh out the world (and its rules/limitations/possible stories) before publishing anything. That’s why I basically write parts 1, 2 and 3 in one go before publishing the first one.

As such, obviously, SPOILERS for those three books. (Although mainly book 2, what this diary is about.)

Also several disclaimers.

- I might switch between present tense and past tense. It depends on when I write parts of these diaries (while I’m writing the chapters right now, or after having done so a few days ago) and it’s hard to be consistent.

- I might refer to Wildebyte as “he”. That’s because the very first implementation of the idea was radically different and had Wildebyte as a young boy. That idea floated in my brain for a while, which is why I sometimes still write that.

- Whenever I talk about future plans or ideas, they are always subject to change. I’m literally writing my current thoughts and process. For example, you’ll notice that I often say “I have this great idea!” at one point in a diary, then say “that idea was rubbish, here’s a better one” a few sections later. That’s the nature of trying to be a professional writer: iteration is key.

What’s the idea?

With each story, I want to …

- Provide a game design lesson (some wisdom I’ve learned after years of making games)

- Teach some computer-related concept

- While playing (or rather parodying) a popular game

Once I had all my options, I sorted the list.

- Most important game design lessons first.

- Easiest/simplest games first.

This was hard to do, so I had to tell myself “just do your best for an approximate sorting, then start writing”.

The consequence? The latter stories were easy to put together. Because they handle a more specific game design lesson, using a more complex game, it wasn’t hard for me to write a quick sketch of a possible plot or problem for the story.

But the first few stories? They were a “lose-lose” situation.

- The game is so simple that it cannot sustain a full story.

- While the lesson is so important (and general) that I really need to think hard about how to communicate or explain this.

That’s how I ended up with the following idea for the second book. I doubted this idea from start to finish, but I had nothing better and just wanted to continue writing. (Additionally, these books are short enough that I feel safe writing absolute trash, and then just throwing it in the garbage and writing something new.)

Rulebreaker Recipes

We are parodying “Fruit Ninja”. (Less famous now, but used to be extremely famous and popular for years as a smartphone game.)

The lesson to learn is about “the game loop”. (A game should be five seconds of fun, which you can repeat endlessly. If you lack feedback, or this loop takes way too long, you’re simply not making a game.)

The computer part we’re discussing is the GPU (or graphics in a very general sense).

Wildebyte enters a new game. This game is a very bland and not-fun made-up game (on purpose!). They notice two things.

- Random objects everywhere are sliced into two parts.

- One of his Lost Memories landed in this game.

They learn that a “Ninja” is terrorizing this game. So they make a deal: I’ll capture the ninja, so you can give my memory back.

As they execute this mission, they learn why the game isn’t fun. (It lacks a game loop. It only has one goal, which is far off in the distance, and no feedback.) They make it fun by actually making the ninja the centerpiece of the game. At the end, they basically recreated Fruit Ninja, and the game is fun to play again.

Chapters 1–5

With this setup, I started writing. As usual, while doing something, the actual ideas and solutions come.

I found a great reason why the game characters won’t just give Wildebyte’s Lost Memory back: when the Camera sees it, the game crashes!

This is great because it does many things at once.

- It’s a new mystery to solve. (Why does it crash? How can we prevent that?)

- It’s directly tied to our main theme (the GPU)

- It’s a simple and clear reason why they’re hesitant to give the Memory back. They even hide it from him while he does the mission!

The first few chapters became …

- Wildebyte lands in this new game.

- Sees the memory, fights for it, can’t get it.

- Learns about the Ninja problem

- Strikes the deal

- Learns a bit more about the game (and why it might not be fun)

This is fine. I continued with this, and it’s okay, but once I reached chapter 5/6 I noticed one glaring issue.

The threat of the ninja is barely noticeable. It’s not devastating (the game just keeps running, even with broken objects) nor urgent.

That makes it a weak conflict to sustain a full story. As such, around chapter 8, I took the time to revise the start anyway.

How do we increase the threat?

- The characters from the game actually close the exit. Wildebyte can’t leave until they’ve fulfilled their part of the deal. (Which means that, if the game crashes or is uninstalled, he is deleted as well.) => this adds urgency and consequences

- The game has a “Core Code”. If that is to be broken, the whole game would immediately be destroyed, with no hope of surviving. It’s hidden deep in the world and cannot be easily accessed, but as the Ninja destroys more and more, they get closer => this adds urgency and consequences

- Early on, mention the possibility of characters being sliced, which means death. As Wildebyte befriends these characters and starts to care for them, this would certainly increase the stakes.

It’s moments like these that help me build out the world. I never even considered a concept like “Core Code” before, but it’s absolutely true for most games. There are parts of the code that are so critical (such as the engine it’s built on), that any change would spell disaster. At the same time, there are many parts in (well-written) code that can fail without failing the whole game.

Similarly, in these chapters I suddenly wrote about a comment the developers left inside somebody’s brain. When I wrote it, I immediately said “THIS IS GREAT, let’s make this a recurring element”. So now comments left by developers are a recurring joke throughout the Wildebyte Arcades ;)

(Also, I realized that—with some small changes—this comment could be a great hint about the solution to a mystery!)

Anyway, with these changes it felt like the Ninja could do real damage and Wildebyte had a strong reason to catch them as rapidly as possible.

How to show the lesson?

This is what caused the most doubts. I know this is a really important lesson, but it’s a very abstract one. “Games should be a small loop of fun”. Yeah, how do we show that?

We need to start with a game that is not fun. One that violates the principle.

First try

At first, I wrote a game that was too mild. It violated the principle, but not enough.

It was basically a watered-down version of Farmville. But with food instead: each character was responsible for growing a different type of food, the player could sell that, buy new food/machines/characters, etcetera.

But you see what I see? That is a game loop! AND WE DON’T WANT THAT!

Second try

As such, I had to make the game even more extreme. There had to be no feedback and no loop. This means …

- You learn (early on) that the game has a huge fifty-step process for reaching your goal. (You start with one seed, grow some food, which allows you to grow more food, etcetera until the end.)

- Any time you reach a new step, however, nothing happens. There’s no feedback, no loop, no tiny rewards along the way.

The trick is, of course, to let the reader know that yes, this game is not fun, that’s the point—while still telling a story that is fun.

That’s the balance this book had to achieve. With a few good mysteries and action scenes, it had to cover the fact that the game (at least for the first 50% of the book) is literally a non-functional game.

Once the game was this extreme, I had to construct a plot that would slowly reveal the issue here.

At the end of chapter 5, I realized the sentence I was looking for: “Journey is more important than destination.”

I had to show that the game loop was about creating a fun journey. About “five seconds of fun” that you can repeat hundreds of times per day. Actually reaching a destination, some goal in the distance, is not what games are about.

As such, I chose the following structure.

- As WB ( = Wildebyte) interrogates/investigates suspects …

- … they show WB their daily routine. That is a game loop, one which they enjoy. (All of them even state that they have no clue about the overall goal of the game.)

Which eventually reveals to WB that the game is about the loop, which convinces them to turn the fun act of slicing fruit into the centerpiece of the game.

More worldbuilding

This also revealed how I wanted to handle the logic of game characters.

I want to be realistic. I want the constraints of computers and video games to force me to write more creative Wildebyte stories.

That’s why the first book establishes the general rule: “When the camera is looking, characters will behave. But when it isn’t looking … who knows what everybody is doing? ;)”

But that leaves a second question: what does it mean for characters to “behave” (when the camera sees them)?

This book answers that. I needed a way to explain the general idea of a “loop” to readers. So I established the following rule: “When the camera is looking, characters can only do what they’re programmed to do. Often, this is a very simplistic chain of commands, which will loop when it’s done.”

This allowed me to write a chapter in which Wildebyte stares in confusion as the characters around them keep looping through their pre-written dialogue, as the camera watches them.

How to explain the GPU?

Another difficult one, although things fell into place rather quickly.

It makes sense for characters in a game to know how these systems work. They are coded to interact with them, they literally live on the device. So most “exposition” about how GPU/Graphics work is simply delivered through dialogue here and there.

To make this even easier …

- This story introduces the Graphics Movers! Those are responsible for adding connections to the GPU. And they obviously know a lot of info about it.

- I planned to visit the actual GPU later in the story.

To hammer home the theme, I decided to lean into the visual side of things even more.

Most games use “GPU instancing”. They create a model only once (in memory), but then copy-paste its appearance many many times. To fill a whole city or forest, without asking too much of the computer!

But this has consequences. Such as: if one instance changes, they all change. Things like that are explored in the story, to hopefully explain even more perspectives on visuals.

Chapters 6–10

See, I have the tendency to overdo it on the storyline front. I add too many. I open mysteries and find out I don’t have time to properly resolve them near the end.

Such struggles always appear around this stage of the story.

To solve this, I always write down the different storylines (or “routes”) I am following. If this list is too long, or they aren’t connected enough, I have to simplify.

Let’s see what we had at this point.

- MEMORY: where is his Lost Memory and why can’t the camera see it?

- NINJA: who is it and how do they catch it? (This is the general detective storyline that powers most of the plot.)

- PAPERBOY: WB changed into the “paperboy” character, what’s the point and what do they do?

- GAME: how does the game work? Why is it not fun and how would they change that? (This is the second main storyline.)

- MOVERS: the rest of the device is still quite angry at WB. They track him closely and warn him to be even faster in catching the Ninja, otherwise it’s the end.

- RESEARCHERS: the researchers (who put him in here) still try to reach him and potentially eliminate him.

Yeah, that’s a bit much. Additionally, you’re always in danger of “overplotting” and missing some emotional core that makes readers care in the first place.

To me, that core is twofold in this story.

- Wildebyte befriends some really nice characters. He finds back some joy and friendship (after losing it in his “real life”), which makes it extra sad when he has to leave them behind at the end.

- Wildebyte yearns for home and is sad about missing it.

I had a third arc about Wildebyte slowly restoring his relationship with the Movers (/rest of the device). But that shouldn’t happen in one book, that should be spread out over multiple books. I could safely cut that.

How to solve this?

I decided to merge PAPERBOY and RESEARCHERS, while moving this to a later stage. (A good way to make a story simpler is by simply starting certain storylines later and/or finishing them earlier. They don’t need to be sustained for a whole story! In fact, that’s what often makes it complicated.)

Only near chapter 10 does the Paperboy actually activate and become relevant. When it does, it’s slowly revealed that researchers try to communicate with him (and the town) through fake news articles on the newspaper.

Similarly, the MOVERS get only a few chapters, and are otherwise a very minor storyline. (I did want to include them for continuation. Otherwise, basically nothing from the first book returned in the second, which felt like a waste.)

At the same time, I made his MEMORY more important.

Initially, I aimed to keep the memory (a Pawn) hidden until the end of the story. It’s just a way to create a clear goal at the start, but it plays no rule during the story. As stated, however, this takes away most of the beating heart of the Wildebyte character.

Instead, WB breaks his promise halfway the book and starts looking for the Memory himself. This allows them to find it earlier, spend time with it, reminisce more about home. It also allows a good character moment: do they care more about home (breaking their promise, endangering everyone by stealing the Pawn) … or are they ready to accept that this world will be their home for a while (and thus play nice and cooperate)?

Chapters 10–15

I took a short break, because I planned to work on some other project during the weekends!

Also because I’ve learned that it takes time to recharge creativity and realize plot holes (or better/more creative solutions). If I write every single day until the book is done, I usually struggle to find creative lines and fun action scenes, because … well … I’ve already written thousands of words and the well of creativity is simply dry!

I realized these other improvements I wanted to make (with another quick revision):

- Now I show how things are sliced/destroyed in the first chapters .. but also how the characters (in this game) have become quite good at rebuilding them. This is boring and also reduces the threat level again! Instead, change the rule to simply: “once destroyed, it cannot be rebuilt”

- I also realized the perfect parody name for Fruit Ninja: “Cookie Kung-Fu”. This also inspired me to retheme the town(which was pretty bland so far) to one made from cookie dough.

- No, wait, I realized I had another story planned (quite quickly) with a Candyland environment. To prevent repeating myself, let’s turn the town into houses in the shape of fruits and vegetables.

Things like this are relatively easy to fix. (Delete and add several paragraphs across a few chapters.) But they make the story so much better in the long run, with a more fresh and thematic world.

As I wrote these chapters, I invented a few creative ideas for scenes (full of tension), which made this part of the story slightly longer. (One more chapter than planned.)

Another reason for this was the addition of Sweettooth and the Cookie Clicker. These are two characters that I want to turn into recurring characters, and will play a huge role in book 3 and 4 as it stands now. (I even mentioned them in the first book.)

Additionally, I was just a bit stuck and felt more motivated to write a funny scene with a weird-talking pirate obsessed with eating that Cookie Clicker :p

Realization: Wildebyte Arcades

As I continued writing, the general idea of the Wildebyte Arcades becomes more and more fleshed out. For example, I knew I wanted the stories to be episodic. (You can read them in any order, there’s no important overall arc.) But I realize more and more that I want it to be episodic to the point of being a loop.

What do I mean by that?

I want to do the same thing in every disk. So when Wildebyte jumps to a new disk, basically everything resets and we start from zero again. They have a voice in their head, again, in book 1. They must learn the rules of this new “device”, again, from the start.

Not only does this lead to cool plans, twists and ideas (which I won’t spoil), it also just makes sense.

Games are just a loop. The core game loop, the one fun action you keep repeating, is the essence of games. The more I think about this and write stories with it, the more I realize how thematic it is to also make it the essence of this whole series.

The major difference? Every time you redo the game loop, you can try something different. So even though everything resets and Wildebyte has similar challenges, they find different solutions (in different environments) which leads to different stories.

(As such, as it’s currently mapped out, there are a few key differences in each disk that prevent things from being repetitive.)

Realization: Game Loops

Unsurprisingly, I had the same revelation for this book. The “game loop” is the “lesson” in this book. (The image you get at the start and end.) So why not structure the whole plot for this book as a loop?

- Wildebyte gets a challenge/goal/obstacle

- They go after it, getting new information or ideas

- Then they encounter the Ninja and chase them.

- Return to step 1

I’d already written the story this way, for the most part. But I initially planned to deviate from this in the ending.I thought: surely we’ve chased the Ninja so often now, I should stop doing it, otherwise it becomes annoying/repetitive. The original plan, therefore, was to write chapters 15 and onward without any chasing of the Ninja.

But I revised that plan, realizing how thematic it was to structure the whole plot as a game loop. I just needed to make sure that every chase of the Ninja felt different and had different consequences.

- The first suggests they’re a black, shadowy figure that lives near Lulu

- The second reveals they can move through walls + almost kills them (by destroying the bridge) + reveals the mysterious building at the edge

- The third reveals there are multiple ninjas + nearly slices Lulu

- The fourth reveals the Ninja can create projections/visual illusions, so they’re often literally chasing ghosts + slices Lulu

- The fifth reveals that there is a real Ninja, as Wildebyte proves that’s the one they’re chasing

- The sixth has a different purpose, now that the character behind the Ninja is revealed, and leads into the climax

Maybe this is a bad idea. But it’s what we’re going with, and experimental ideas are fine if applied to a single book (in a series that might span 20+ books in the end)! I will not use this structure again in the next 10 stories.

Chapters 15–20

During these chapters, I actually uncovered another solution to the mystery. One that perhaps was even more interesting. (So far, I had worked with the revelation that Lulu was the Ninja.)

- The game is being influenced by the researchers (who want Wildebyte gone)

- They designed it to lead to Wildebyte’s capture and demise.

- Which means everyone is the Ninja, except for him and Lulu.

It’s a very interesting solution to a mystery like this. In the end, however, I decided to stick to my original plan. I would have to change a considerable amount of the story to set up this new revelation. And I think it would diminish the other parts of the story, making this more like a “shocking twist” than a satisfying ending.

I did mention it, however, to put the Wildebyte on the wrong track for a few chapters. Because it is an interesting theory.

But for now, I kept this idea (of “there isn’t one criminal; everyone is the criminal except for one”) for perhaps a later story …

Also, I initially planned to make the “reveal” of Lulu being the Ninja at a later chapter (20 or 21). But as I was writing, I realized this wouldn’t work as well.

- I’ve given basically all information you need. Anybody who has been paying attention, will probably be pretty certain Lulu is the Ninja now. So no point delaying it further.

- Wildebyte visits the GPU at chapter 20 (and the surrounding chapters), which means he is away from Lulu. Having the revelation then is less impactful than when he’s literally standing in front of her.

- There are several storylines to wrap up. I know (from previous stories) that the climax can easily get muddled when you try to resolve too many things in one chapter (leading to basically 3 climaxes instead of one).

For all those reasons, I decided to move the reveal a few chapters forward.

Besides that, these chapters were honestly tough to write. I was most uncertain about these and the specific information I wanted to give/reveal/portray. The story was coming to an end, but we’re not actually at the end, which is always the hardest part of a project.

In the end, I told myself to just keep writing a few chapters a day and pull through. Usually, when you get going like that, the “good” ideas present themselves automatically.

Stakes in episodic storytelling

As I gain experience with writing stories in many, many parts … I realize we’ve lost one very common way to add tension and stakes: does the main character succeed or survive?

Because the Wildebyte is episodic and will have many parts, it just doesn’t work to pretend their life is in danger every time :p You know that there’s another book. You know they survive and they don’t get out of their game.

So how do I actually introduce stakes? How do I make things exciting and worth worrying about?

I’m slowly finding the answers.

- Add other characters whose fate is not certain at all. (I’m thinking of adding some sidekicks that might tag along for a part of the books. Those can die, go away, change, whatever at any time.)

- Make the story about some permanent change. (To the device, to Wildebyte, to a game, etcetera. But this change can’t be too significant, because then it wouldn’t be episodic anymore! Then I’d have to factor in the change in every subsequent book.)

In other words:

The Wildebyte books should really be about things/characters that Wildebyte cares about, instead of themselves

I shouldn’t put their life in danger or dangle the idea of “Wildebyte might get back to his real life in this book!” in front of the reader. Or, at least, it shouldn’t be a focal point. It can be a solid goal—as the Wildebyte is obviously trying to survive—but the story needs to be satisfying, even if you predict they’ll survive and stay in Ludra.

Every book will probably involve Wildebyte trying to get one of his memories in hopes of getting back. That’s like a given. But it should be a subplot.

The biggest plot should be something else.

- He learns to really enjoy a game on the device, and now it’s threatened with removal!

- He befriends characters, and now their life is in danger!

- He can only get his memory by doing some other (more important) mission for the game!

I’ll probably learn more tricks for writing stories in this structure as I continue. But the main lesson remains that the stories should not be about the Wildebyte. They should be about the specifics of the game they’re currently in—and it’s my job to make the reader care about each new game and character.

Chapters 20–end

Not sure if all of this is believable or “earned”. (I often have this struggle with the most emotional moments. Always feels melodramatic the moment I write it, like there wasn’t enough setup.) But I think the solutions to most problems are very good and thematic, and it’s at least adequately written.

The GPU was a struggle to figure out. How to represent that? Add even more types of Movers?

In the end, I came up with something that’s mostly fun and accurate, without slowing down the plot too much. After writing it, however, I did note that it’s a bit bleak and bland. So, for the revision, I planned to make the GPU a more colorful and graphically unique place.

The ending of this book turned into two chapters, really. There was a lot to tie up, and it feels very rushed and overwhelming to do that all in one final chapter. So I broke it into two parts.

Additionally, I want to experiment with how I end these books. I don’t want to end every single one with “oh no, Wildebyte is in danger again, so he runs into the first random game he finds! The end, see you next book.” I want to vary it. I want them to regularly make a conscious decision about where they go next. I want to tease a little more, perhaps add cliffhangers.

That’s what I’m experimenting with in this ending. He gets a longer conversation tying up the themes of this book, but also setting up his connection to Ludra and the Native Entities. They don’t trust him, but they need him. There are larger dangers looming, and they give him the job of fixing the broken games.

It gives a clearer goal for the Wildebyte. I also think their relationship with the device (and those Native Entities) can actually be a very strong recurring part of the books, which is why I wanted to end on that note.

All in all, I usually rush a bit through the ending. (I think “if I just keep writing for an hour or two, this book is done” Which causes me to write 15,000 words in a day, and surely those last 5,000 words written late at night can’t be as good as the others :p) I left quite some notes for myself to improve things in the revision.

A … cardboard disk?

When I conceived this idea, it was clearly meant for video games. I dismissed the idea of creating stories around board games so fast that it basically never occurred :p

But as time goes on …

- More and more board games can also be played digitally, which is usually really fun and works well.

- The board game scene expands and expands, growing more popular and creating hybrids with video games. (As I have often done as well. For example, a game that’s played with a board, but also using an app or a website.)

- I realize I need to tweak more than I thought to make the stories work anyway. (If I wanted to strictly play by the rules of computer logic, it would be near impossible to tell any satisfying story.) Well, if we’re not going to be extremely realistic about it … why not add stories about board games as well?

I’m still not sure whether this is a good idea. Board games are less popular, and they are harder to turn into stories. For example, take a card game. How do you put Wildebyte inside a card game? It’s a big ask (of the reader) to imagine cards as main characters with feelings and stuff :p

As such, I merely wrote down some initial ideas, but have no concrete plans. As I see it now, these stories would never be part of Wildebyte Arcades. They might be their own series, or just some silly short adventures I publish for free.

Because I can see cool stories around Wildebyte playing a game of “Risk” or “Catan”. There are numerous board games with a more defined setting or even characters to play, which lend themselves to stories in such a “Cardboard Disk”.

Anyway, ideas like that pop up as I write more Wildebyte stories.

Finishing

To give you an idea, I spent 5–6 days writing the story, with one day revising in between. (Remember all those little notes about what wasn’t really working? I took one day to revise the whole first half of the book and rewrite all that.)

This is extremely fast and not common. Other books will probably be slower. Or they should be, as the downside of writing this fast is that your creativity and prose suffer just a bit. If I’ve already written 5,000 words today, my next scene won’t be as sharp and witty as if I had gone to bed and written it after waking up the next morning.

Because this pace means I wrote on average 8,000 words a day. And that does not include this diary, marketing material, other projects I work on, etcetera.

As such, I was completely (mentally) prepared to do a HUGE revision later. I always leave the story alone for a few months, then come back and the issues I’m having with it. These often end up being crucial changes that really improved the story, even if each change only took 5–10 minutes to fix.

If you know this pace is ridiculous, why aren’t you slowing down? Like many writers, I have this overwhelming urge to get stories out. I can’t tell myself to stop after writing some reasonable quotum of words (like 1,500 a day). Because what am I going to do the rest of the day? Just think about all the scenes I could have written, but didn’t, because I imposed some arbitrary limit on myself! I end up writing the scenes in my head anyways, as I watch a movie, stand in the shower, exercise, etcetera.

There are days when I write 100 words. There are days when I write 10,000 words. I let creativity (my “writing muse”) guide me, with the only restriction being that I do write something every day.

The other reason is that the Wildebyte was always meant as short books that do not take me too long to write. That’s the original thought that started this whole adventure: I invest so much time and effort into these big ideas for books—I just want a project that allows for quick, light-hearted adventures!

When viewed in that light, you might consider a Wildebyte Book a failure if it takes more than three weeks to write it. That probably means I took it too seriously or got stuck because the story just wasn’t working.

Revision

Anyway, the main changes in the revision were …

- Add more “suspicious hints” to all characters, to really get that mystery of “who’s the Ninja” going

- Take the overarching game to an extreme (more than I already did). The whole point of the game is that the original game is boring and doesn’t work. If I make the game too fun or complete at the start, this whole point is moot.

- Some inconsistencies about how I named things, where people were at certain times, or descriptions. (Otherwise a general lack of visual descriptions, as I tend to have in my first draft.)

- For example, the beating heart of the game used to be called Core Code, but that’s a bland name and requires two words. So I wrote a note to myself to rename it to Soulcode or Codeheart.

- Some ideas that weren’t explained enough, in my view. Especially reveals in a mystery like this—and computer concepts I try to include—really need to be clear to the reader. With clear language and every step neatly laid out.

These revisions are to make the story better, not perfect. After toiling away at improvements and rewrites for a while … I just tell myself it’s done and I have to move on. As the conclusion below will explain, perfect doesn’t exist anyway, especially not for creative people.

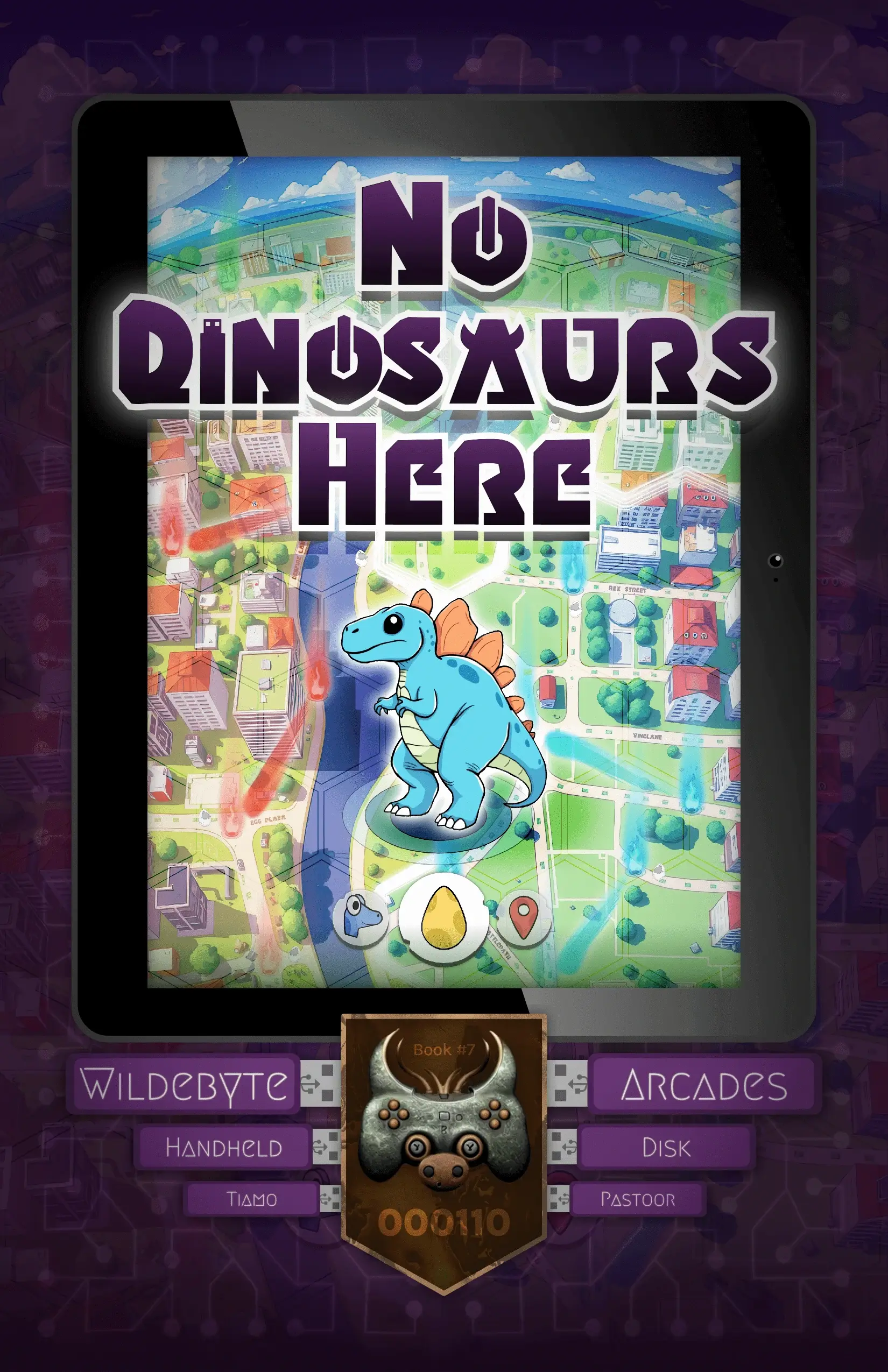

Designing the cover

I didn’t document the entire process for it, but I still wanted to share my thoughts on the book cover / illustrations for this one.

When I designed this cover, it had been over 6 months since I designed the first one (for the first Wildebyte novel). This meant I had forgotten some things I shouldn’t have.

- The upper part of the image will be obscured by the book’s title.

- Covers are obviously in portrait mode (A5 / Letter format), while games are usually played in landscape mode. This made my initial ideas or visualizations pretty much useless.

- There is a lot around the main image of each cover. (The tablet. The electrical lines. The metadata saying “Wildebyte Arcades, by Tiamo Pastoor, etcetera”) This means the image itself needs to have a clear focal point, but also needs to work as a background.

My initial attempt was to just show a ninja dojo and the ninja character from the game slicing things up. This looked weird, however, in portrait mode. (Way too much space at the to and bottom, with no good way to fill it.)

So I thought: “wait, the whole story is about how the ninja slices stuff in half … what if we create a cover that is sliced in half?”

That’s how the idea started to create a sharp line down the middle, and stitch two contrasting worlds together. This already worked much better, though it remains a bit … experimental.

The top world would be more important (and oriented correctly) … but now I realized that the text would completely cover the most important bits.

After shuffling around and resizing elements, I decided to just rotate that painting. The ninja dojo is fully visible (albeit upside-down). The other side, which is way more boring and empty, is mostly obscured by the book title.

Finally, it all became a bit messy. There were multiple ninjas, lots of sliced fruit, other characters from the book positioned around town … it didn’t look cohesive. The viewer didn’t know where to start looking!

So I created a focal point. One ninja, placed centrally, much larger than the others, with loads of effects around it to make them seem more powerful and magical.

As usual, all of this was a combination of AI generated imagery and manual illustration / design. The AI doesn’t understand what I want, especially not to this level of detail. I also can’t just copy-paste random stuff on top of each other and expect it to work.

I have to add shadows, recolor objects, modify their clipping / contrast / brightness / perspective, all to make them fit within the scene as if they were always there.

On their own, they’re all quick fixes or simple steps. But you have to know they exist and consistently apply them. For example, the score on the floor is obviously distorted to fit perspective and recolored to fit the lighting / general color scheme. If I’d just plastered a piece of text on there, it would have looked awful. With these simple tweaks, the score counter on the floor looks like it belongs.

One thing that made a huge difference was to add a trail to the sliced pieces. (It was the last tweak I did.) At first, the sliced fruit looked fine, but a little too static and clearly pasted. (As in, it’s plastered on top of the background as a separate sprite.) By adding a slight particle trail—as most games do—they seem to move and get their own place in the picture.

With that, my laptop nearly buckled under the weight of so many images and effects, so I had to stop and call it done.

In the end, I think the cover is very colorful and impressive, and just below the threshold for being “too busy” or “too childish”. At least, that’s what we’re going for. As I write more books and design more covers, I will probably refine this further.

Conclusion

As I mentioned, I doubted this story from beginning to end. But you know, I’m an artist, a perfectionist, a doubter, so I’ve learned to write the thing anyway.

(The general thought here is: “I can finish a whole Wildebyte book in 1 or 2 weeks. If it’s totally trash, that’s fine. I haven’t wasted much time, and I learned a lot from the attempt.”)

The final story is certainly … unique. It has a bit of an odd setup and mix of storylines, as I try to figure out what I want the Wildebyte series to be.

At the same time, I have enough experience to make the story fun anyways. I, generally, adopt the mindset of a chameleon. (“I’ll just take whatever I have and make it work. Give me a weird setup for a story and I’ll adapt.”)

This means I rarely end up writing a story that I deem too bad to publish. It also means I sometimes try way too hard to make a “mediocre idea” work. To squeeze gold out of a pile of garbage :p

Only near the end did I realize “wait a minute, wouldn’t a DRAWING game have been a much better fit for the first book that explains graphics?”

When such a thought appears, I usually feel stupid and defeated. Duh, that would’ve been the obvious choice! At the same time … is it though? A drawing game has no characters and almost no depth. How do you write a story around it? I’d have to invent lots of extra ideas and characters anyway, so meh.

I ended up writing down an idea for such a story, but it became so complex and “out there” that it wouldn’t feel right for a second book anyway.

In the end, all we can do in life—just as the Wildebyte—is fail forward. I just keep writing these stories, even if I doubt them all the way. Because writing something is better than writing nothing, and publishing a bad book is better than not publishing these stories for the world to read at all.

As I slowly release all these stories, we’ll see if others share my doubt.

Until the next diary,

Tiamo Pastoor